Japan has all the answers you need

TMC#16! Lower real interest rates and credit creation help generating (the illusion of) increasing wealth: can it go on forever? Japan says ''not really''.

15’ reading time

Good morning everybody and welcome back to The Macro Compass!

If you are not subscribed yet, here you go!

Today we look at Japan, a country which has:

Embarked in (once considered) unorthodox monetary policy already 20 years ago

Continuously run fiscal deficits (yes, really) since 1993

Been the first to experience a relentless drop in risk-free real yields

Endured the effects of a poor labor force growth already in the ‘90s

Although no economy is the same and there are relevant differences between the Japanese and the US or European macro setup, we can learn quite a few things by studying what happened in a jurisdiction that experimented with QE and ‘‘QE + fiscal’’ already 20-30 years ago.

Ready? Let’s dive right in!

Nobody likes a shrinking pie

If you forget about cycles for a moment, our economic system (the pie) is structured to grow organically as few factors (the main ingredients) interact together.

The main ingredients are labor supply and total factor productivity.

Japan was one of the first large developed economies to run out of the ‘‘labor supply growth’’ ingredient. As you see from the chart below, Japanese labor supply growth (purple dotted line) was already declining sharply in the ‘70s-80s.

Small intermezzo: yes, both Western European and Northern American labor supply growth after 2020 will be flat or even negative.

Ceteris paribus, the pie would not only stop growing at a decent pace…it would actually shrink. Productivity is required to keep the pie from not shrinking.

Back to Japan in the ‘80s.

The pie was still growing, but at a shrinking pace: labor supply growth trends were declining and total factor productivity was decently stable around 1%, but that’s it.

And that’s when Japanese authorities decided to go for large credit creation.

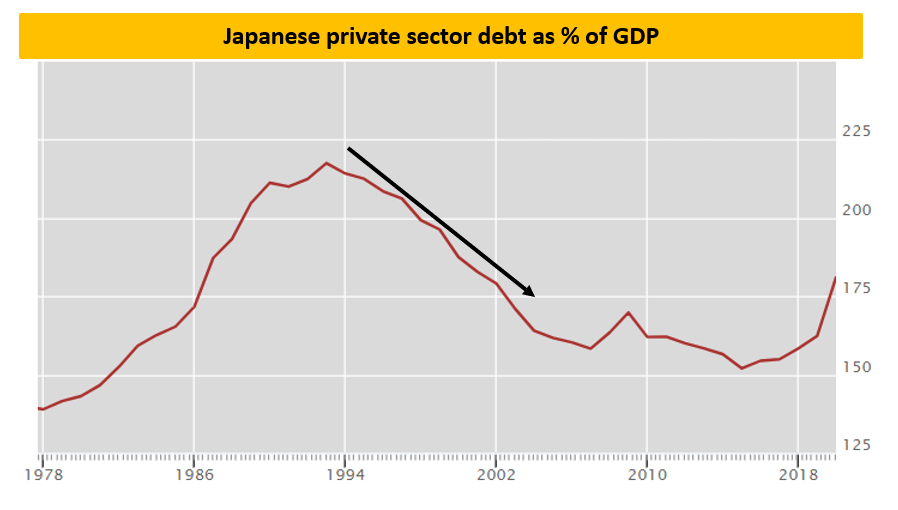

Between 1980 and 1993, Japanese private sector debt as % of GDP increased from 140% to 218%. That’s outrageously quick credit creation towards the private sector.

The public sector was not stingy either, as the Japanese government ran budget deficits for those 13 years too at an average of around 2% of GDP per year.

Proper money printing here!

So, what happened to GDP and asset prices?

House prices in real terms increased by 72% in 13 years.

The Nikkei 225 rose by 500% (excluding dividends) between 1978 and 1990.

Real GDP grew 3.6% per year on average despite a slower pace of growth in labor supply and total factor productivity compared to previous decades.

Core inflation between 1982 and 1992 was on average +2.4% per year.

Money printing (the proper one, not QE) works!

Well, it’s not that simple…

Where’s the trick? It’s a fragile system

Large amounts of credit creation for relatively unproductive purposes in a short period of time generates inherent instability into our economic system.

See, the private sector needs real earnings and cash flows to service the increasing amount of debt it underwrites during periods of sharp credit expansion.

Ideally the private sector would sit on debt servicing costs (real interest rates + credit spread) equal or lower than the real earnings or cash flows it can generate.

But the BoJ was worried about inflationary prospects, and it sharply raised interest rates at the end of the ‘80s.

2-year risk-free real yields in Japan were >6% at the beginning of the ‘90s.

The private sector does not borrow at the risk-free rate, but it pays an additional credit spread on top.

Households were refinancing increasingly larger mortgages at 7-8% real yields.

Corporates were refinancing larger debt burdens at similarly high real yields.

The private sector went under large pressure, and it started deleveraging.

As asset prices collapsed across the board and defaults started picking up, employment prospects worsened and the Japanese private sector went into a deleveraging mode.

If credit creation prints money, deleveraging destroys money.

Throughout the ‘90s, the Japanese private sector went through a ‘‘balance sheet recession’’ as Richard Koo calls it.

Private sector debt as % of GDP shrank from 215% to 160%.

Despite efforts from the Japanese government to provide resources to the private sector via budget deficits throughout the ‘90s, real GDP grew at a miserable +0.5% per year on average.

Time to try something new…

‘‘Fiscal stimulus + QE’’: that must work!

At the end of the ‘90s, Japan was experiencing mild deflation: core CPI YoY was flirting with the 0% line and sometimes printing in negative territory.

The BoJ decided to announce the very first QE in 2001.

Surely banks would lend more, and private sector credit creation would kickstart again and deliver higher wages and a pick-up in inflation too.

Not really.

Between 2001 and 2006, the monetary base doubled (courtesy of QE expanding the BoJ balance sheet) but bank loans shrank (!) by 25%

Banks don’t lend if loan yields are low, the borrowers’ creditworthiness is debatable and regulation is tight. Their RoE prospect versus credit risk they would take onboard is simply too poor.

Well, if the private sector won’t borrow and banks won’t lend…we will fix it via the public sector.

Non-stop budget deficits and QE on top.

‘‘Fiscal + QE’’ ought to work, right?

Japan has been printing budget deficits to the tune of 4-5% per year on average for the last 20 years, and it has been doing QE too.

Since 7-8 years, the ‘‘debt monetization’’ is in full shape: BoJ purchases are even larger than the net borrowing requirement from the Japanese government.

Risk-free real yields have ranged around 0%, and been negative for most of the time.

What’s not to like here for the ‘‘fiscal + QE’’ crowd?

And still, between 2000-2020 (‘‘fiscal + QE’’ period) Japan has recorded:

+0.6% average real GDP growth per year

-0.2% average core inflation per year

It doesn’t seem to do all that magic, after all.

Why?

If the private sector refuses to lever up, the public sector has a hard time picking up the entire credit creation bill.

And even if it does, this credit is sloshed into the private sector without signs of healthy credit demand.

The private sector might decide to offset public credit creation by saving the newly created money or using it to pay back private debt.

Lessons learnt and what’s next

Japan has been a pioneer in both credit creation and ‘‘unorthodox’’ monetary policy.

By looking at their 40+ combined years experience in both fields, we learnt that:

When the economic pie starts shrinking, authorities go for sharp credit creation

Sharp credit creation with organic participation from the private sector leads to increased asset prices, but also to a pick-up in GDP and inflationary pressures

Additional leverage bears increasing debt servicing costs; if real yields are not kept in check, the system breaks

If the private sector refuses to participate in credit creation, ‘‘fiscal deficits + QE’’ can only be a suboptimal band-aid to keep the system afloat

What’s next and what about other jurisdictions?

I am going to leave you with two charts…

While EU and the US managed to lever up the private sector in the 90s and early 2000s, Japan was undergoing a deleveraging exercise.

Since 2008 though, the private sectors in EU and US have refused to lever up additionally - and that’s quite important, as we have noticed earlier.

Following the Japanese example with a bit of a lag, real yields in EU and US have also dropped materially and now flirting with the -2% area.

The most interesting part of this chart is the red arrow, though: Japan did not manage to keep real yields on a declining trend over the last 6-7 years.

And we know what happens when the private sector is overleveraged and real yields don’t decline anymore.

Can the EU and the US fix this?

One final word: CBDC.

We are now a 6.500+ community here on The Macro Compass. Thank you all!

If you liked this article, why not share it with your (social) network?

If you are not subscribed yet and you’d like to receive updates directly in your inbox, you can subscribe clicking on the button below.

I generally publish 1-2x a week (Monday + sometimes Thursday) covering market developments across asset classes and digging deep into broad macro topics.

For free, without ads.

See you at the next update!

Hello Alfonso. All along the reading of you article I have your last word in mind, how funny.

What's your stance on the Fed (and other central banks I suppose) pushing to short-circuit the split money system (i.e. central bank money and Com. bank money) through the introduction of CBDC?

In very particular, the influence (since exactly 09/2019 during the repo crisis) of the reserve deposit (per Fed: "Liabilities and capital: liabilities deposit") on the previously unaffected retail deposit (per Fed :"deposit, All commercial banks"), for the latter was growing steadily and independently of the central banks' money the past 40years+. Both derivatives seem to follow the same law.

By driving up demand for treasuries (pushing real yield down), I believe that the central banks are pushing to get more "tools" to respond to the next downturns, and not only by playing with interest rates anymore. I believe they try to find a way to "go direct" in accordance with the talks of 'BlackRock' by pumping the stock market with all that QE money. I also believe that we have just entered the "QEternity" like you mentioned last time in order to make those big monetary policy moves in the next decade, likely resulting from propositions to deal with a possible "dramatic" downturn. The latter that could be 'cooked up' and gather momentum as we speak through this burning tightrope we walk on (market doubling with poor economic basing).

I guess your stance will be given in the next post! See you then.

What are the sovereign debt servicing costs as a percentage of GDP for Japan USA EU etc ? I have heard that for Japan it is 4% GDP but I do not know where I can check this for accuracy. Another great post by AP.