Money velocity hasn't fallen much: wait, what?

TMC#13! Money is a complex concept in modern finance, and we like to simplify things using M2 + ignoring financial transactions: that's not the way to do it.

Good morning everybody and welcome back to The Macro Compass!

This week we will talk about the ECB meeting, the market action last week and why ‘‘money velocity’’ hasn’t magically disappeared but its drop is the result of how outdated M2 is and how wrong it is to exclude financial transactions from the equation in 2020.

A quick reminder to subscribe to my free live Q&A Zoom Webinar that will take place on Wed 28 July at 19.00 CET (13.00 NY time). Steps are pretty simple:

Register to this free newsletter (if not done yet)

Share this article via your preferred social media channel

Reply to this newsletter email (or to the welcome email if you just subscribed) with a ‘‘yes’’ and a question you’d like me to answer

Few spots left really!

Also, my interview with Real Vision is now freely available on Youtube (link here). If you want to know more about my macro views, you can also check out this podcast I recorded with Market Champions (Spotify and Apple, also on Youtube).

The ECB just told us EUR rates will be negative forever

This is me watching the average ECB meeting.

But last week actually I did not need 3 espressos to manage it. There were some pretty relevant things said by Lagarde.

The bottom line is: QEternity and we will never hike.

The new hurdle to tighten monetary policy seems to be the following:

Actual inflation prints are converging to the 2% level already today

Inflation forecasts during the projection period (read: 2-3 years) need to be pretty much at 2% or above for the full forecast period

Inflation actually prints durably above 2% matching ECB forecasts

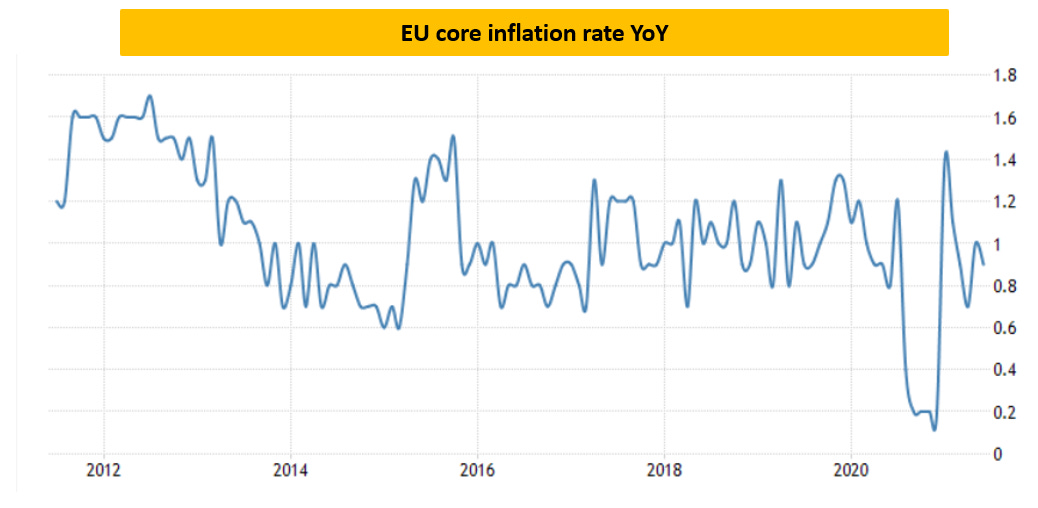

Now, here is the track record over the last 9 years.

Zero (0, null, nada) EU core inflation prints >2%.

Imagine the ECB being able to project inflation at or above 2% for 2-3 years, CPI to actually print around 2% and to consistently remain there for a while.

How many chances would you give to such a setup?

The market reaction was pretty much textbook: yields dropped, bonds outperformed swaps, the curve flattened a bit and measures of term premium compressed.

The term premium measures the compensation required by investors to own long-term bonds rather than owning short-term bonds and rolling them. In principle, the expected return from rolling over a series of short bonds with a total maturity equal to that of the long bond should be the same as the return from owning the long bond.

But this ignores that investors holding the long bond face duration risk and uncertainty about the future path of interest rates, and hence they generally require a ‘‘term’’ premium.

The ECB basically reduced the uncertainty about the distribution of possible future path for interest rates in the Eurozone. Lowering them is relatively difficult due to the vicinity to the effective lower bound, while raising them is now basically impossible due to the new forward guidance and the poor structural inflationary pressures in the Eurozone.

The base case scenario of low rates for a very long period of time is now even more probable, hence investors require less term premium to own long-term bonds = flatter curves and less implied volatility in the EUR fixed income market.

Why is this relevant for global markets?

The ECB is on a clear mission to lower real yields in the Eurozone by keeping nominal yields very low and try to ‘‘talk up’’ inflation expectations. Lower real yields in EUR push EUR/xxx down ceteris paribus.

Here is a chart of EUR/USD and real yield differentials:

As EUR real yields drop relative to USD real yields (orange line down), EUR/USD tends to drop too (blue line). This is because the relative compensation for owning EUR in inflation adjusted terms is now less than owning USD => capital flows from EUR to USD, leading to EUR/USD depreciation.

Now, in a disinflationary/slow growth world there is virtually no jurisdiction that likes their currency to strengthen against peers as a result of higher real interest rates on a relative basis.

Everybody wants a piece of the shrinking growth and inflation pie, and they can compete for some of it via the real yield/FX channel.

Watch out for ‘‘real yield wars’’, also known as FX wars.

On another note, secular trades still alive and kicking last week with:

Nasdaq overperforming Russell by another +1.2%

SPX overperforming Emerging Markets (EEM) by another +3.5%

Bond yields stubbornly low

No changes in my assessment: we are in the secular Quadrant 1.

Please stop butchering ‘‘money’’ and ‘‘velocity’’

‘‘Money velocity’’ is dropping. You must have heard this at least 300 times already.

This assessment is based on outdated, almost useless definitions of ‘‘money’’ and ‘‘velocity’’ for a highly financialized economy where QE is a standard monetary policy tool and financial transactions can’t be ignored.

Without going too much into details, M2 is a lot about bank deposits. The idea is that bank deposits represent a ‘‘real economy’’ form of money as they can be withdrawn/spent at any point in time.

M2 increases are often used to call for major inflationary pressures to come: too many deposits out there, they will sooner or later be spent (‘‘velocity goes up’’) and an inflationary spiral will start as there is too much ‘‘money’’ chasing the same basket of goods. But despite M2 having almost 5x in the US between 1994 and 2020 we haven’t seen US turn into Venezuela yet. So, where is the catch?

I will sooner or later publish a primer on the different forms of money, but for now you have to know that not all bank deposits are the same.

When QE takes away a bond from an asset manager or a pension fund, this non-bank financial institution will deposit the proceeds in a bank account by default. We have more bank deposits in the system now, and…how is an additional bank deposit from a pension fund supposed to do anything to growth and inflation?

So, M2 is perhaps not the most comprehensive measure of ‘‘money’’ once QE becomes a standard monetary policy instrument - especially if you want to get any clue about future growth and inflation.

The other point I’d like to make is that velocity assumes all money ends up in transactions which directly affect GDP.

While this was mostly the case in a non-QE and non-financialized economy (think 1940s-1980s), you can’t say the same today.

Financial transactions and wealth effect are an obvious candidate for some of this ‘‘forms’’ of money to flow towards.

The chart below shows US M2 (orange, indexed at 100 in Mar 1994) versus US GDP + a financial basket (blue, indexed at 100 in Mar 1994). The financial basket includes stocks, bonds and real estate.

In grey, the ‘‘new’’ money velocity defined as (GDP + financial basket) / M2.

Pretty stable, isn’t it?

Money is quite a complex animal - stay tuned for updates!

If you liked this article, why not share it with your (social) network?

This community is growing very quickly, but still…The more, the merrier!

You can share on several platforms clicking on the button below.

If you are not subscribed yet and you’d like to receive updates directly in your inbox, you can subscribe clicking on the button below.

I generally publish 1-2x a week (Monday and Thursday) covering weekly market developments, posting trade ideas and digging deep into broad macro topics.

For free, without ads.

See you at the next update!

Another excellent article Alfonso. Thank you.

Also enjoyed watching your interview with Daniel L on RV recently. I noted his call out on 'official' inflation and 'real' inflation. Of course, if the market only reacts to official inflation, then it doesn't much matter what real inflation is for the time being.

But, that all depends on the magnitude of downward pressure on peoples purchasing power and over what time period. A tricky monetary, fiscal and political game that has the real potential to blow up globally in the form of nationalism and populism. The skinny end of the wedge is already in position.

The correct investment mix based on multiple extreme outcomes is critical.

As a econ phd student having done my macro courses where the financialisation of monetary policy is absent from curriculum and everything we get taught is basically what you here call the 1940s-1980's framework, I find this blog a wonderfull educational ressource. Thanks!