Pelley: “Where does it come from? Do you just print it?”

Powell: “We print it digitally. So as a Central Bank, we have the ability to create money digitally.’’.Jerome Powell - ‘‘60 Minutes’’ interview, May 2020

In a famous interview released on May 2020, Jerome Powell stated Central Banks can print money in digital format.

And he is right, they indeed do that when they embark in policies such as QE.

But he forgot to mention that what they print is bank reserves, which is money only for commercial banks and not for us common people.

And that these bank reserves don’t have legal tender, they can’t be used to transact in the real economy and most importantly they never reach the private sector.

Never.

Running a large fixed income book for a big European bank for years, I have personally been on the ‘‘receiving end’’ of the QE trade - I am very excited to try and convey some of the experience and knowledge accumulated throughout that period!

In this article, we will answer the following questions:

If Central Banks only print digital bank reserves and not real economy money, why do they engage in QE in the first place?

If bank reserves are not money for the common people, what are they useful for then? What can commercial banks do with bank reserves?

The ‘‘Portfolio Rebalancing Effect’’ Explained

Actually, before we jump right in.

If you are a macro enthusiast based in the US, pay particular attention here!

Being aware of how complicated it can be to translate a macro view in action as often you need complex derivatives contracts, I wanted to flag that a company named Kalshi is offering a neat solution to that problem.

Kalshi offers event contracts, which are "Yes" or "No" shares tied to specific future events — think of the May CPI report released on Friday: if you have a macro view on inflation, you can directly translate it into action!

They have markets on various strikes for what the MoM inflation rate will be, ranging from 0.1% to 1.2%. If you have a view that inflation will surprise on the upside or on the downside, you can buy ‘‘Yes’’ or ‘‘No’’ shares directly tied to that outcome.

I definitely recommend to check them out (link here).

Now, back to it: Central Banks create bank reserves when they perform QE.

But if bank reserves are just money for banks stuck in the financial system, why would they bother to do that in the first place?

Mainly because of the many channels through which QE helps generating the so-called Portfolio Rebalancing Effect.

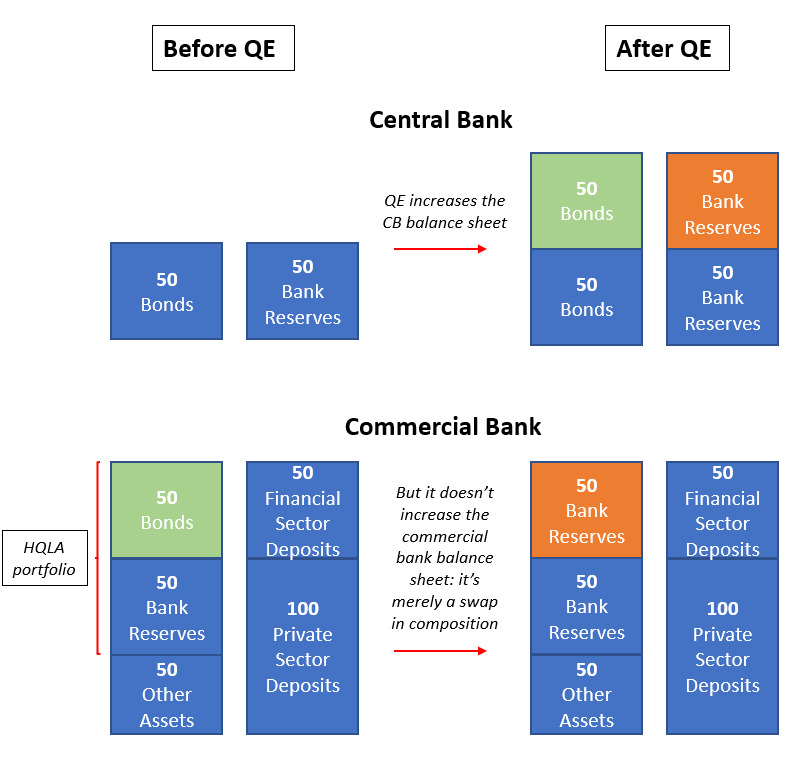

To understand this, let’s start from what QE does to the balance sheet of a commercial bank.

When a Central Bank performs QE and directly buys bonds from a commercial bank, they merely change the composition of the commercial bank asset side by reducing the amount of bonds they own and instead increasing the amount of reserves.

No new spendable money for the private sector has been created in the process, as commercial banks don’t use reserves to make new loans.

So why the heck would Central Banks embark in QE and forcefully change the portfolio composition of commercial banks in the first place?

In short: to encourage them to rebalance their portfolios towards riskier assets.

How does this work?

Let’s go through it together.

Historically, commercial banks own a portfolio of bonds because:

A) Regulators incentivize them to do that;

B) Bonds are interest-bearing and liquid instruments which are also widely accepted as collateral: all very desirable features for a bank;

C) They serve as a hedging tool for the interest rate risk of their liabilities.

Now, QE is taking away these bonds and flooding banks with reserves instead.

Let me show you why reserves are a sub-optimal asset to own for a bank, and hence why they’ll instead tend to rebalance their portfolio towards (riskier) bonds.

There are 3 main reasons.

#1: Regulators have made bonds (almost) as ‘‘regulatory-friendly’’ as reserves.

After the Great Financial Crisis, regulators realized that commercial banks weren’t always owning enough liquid assets to survive a sudden spike in deposit outflows and therefore implemented a new regulatory constraint: the Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR).

It basically forces banks to own enough High Quality Liquid Assets (HQLA) to be able to meet an avalanche of deposit outflows during a stressful period (e.g. bank runs).

European and US banks are now forced to own about $12 trillion (!!!) of cumulative HQLA assets at any point in time.

Sounds huge, it is huge.

Curious to know what’s eligible as High Quality Liquid Assets (HQLA)?

In yellow, our usual suspects: bank reserves and government bonds.

But the orange boxes contain some interesting information, too.

Subject to a maximum of 15% of the total HQLA portfolio, BBB corporate bonds, mortgage backed securities and even certain stocks (!) are HQLA eligible.

By making bank reserves and (riskier) bonds virtually inter-exchangeable from a regulatory standpoint, regulators have vastly increased the marginal appetite banks have for ‘‘regulatory-friendly’’ HQLA bonds.

After all, if for regulators these bonds are as good as reserves and they offer a higher yield on top…why not?

#2: HQLA-eligible bonds carry higher yields than bank reserves.

The chart above shows the 2 to 10 years yield curve for bank reserves at the Fed (orange) against two forms of regulatory-friendly bonds: US Treasuries (blue) and US BBB-rated corporate bonds (green).

US Treasuries already yield more than bank reserves and they have a very liquid secondary market, a deep repo market and they are considered as the best collateral available out there - quite a no brainer!

BBB Corporate Bonds offer an even higher yield, but there are some trade-offs there: the higher yield must be measured against the additional credit risk, some small regulatory haircut, a less liquid secondary market and a less deep repo market.

From a risk and liquidity-adjusted return perspective though, one can argue HQLA bonds are generally attractive vis-à-vis bank reserves.

#3: Bonds can be used to hedge interest rate risk, while bank reserves can’t.

Finally, let’s quickly cover interest rate hedging.

The liability side of commercial banks balance sheet is mostly composed by customer deposits, and generally these customers can decide to walk away with their money whenever they prefer.

Risk departments within banks are tasked to calculate the average tenor of customer deposits and other liabilities sitting on the bank’s balance sheet such that duration mismatches can be mitigated from the asset side - for instance, purchasing bonds with a certain offsetting duration.

On the other hand, bank reserves are an overnight instrument with no duration and hence they are not useful to hedge interest rate risks.

The important bottom line is that while preserving many useful features, bank reserves are a zero-duration and low-yielding instrument which can be suboptimal to own in big sizes especially as regulation (HQLA) has become very friendly towards certain bonds.

Here is a useful table to compare bank reserves and HQLA-eligible bonds.

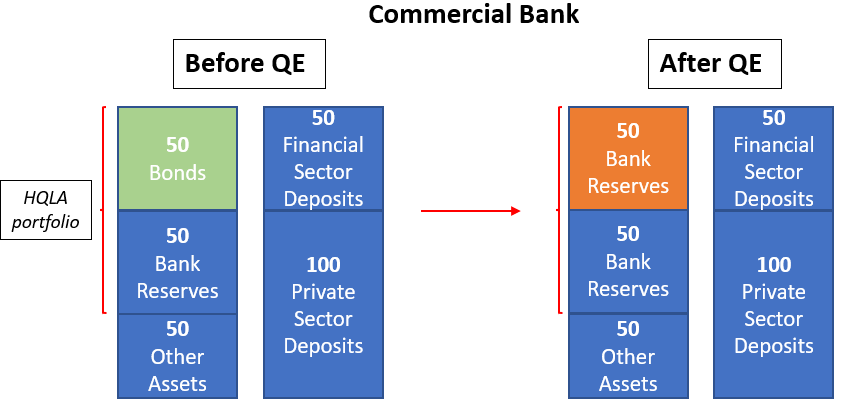

Now that we have established how undesirable it is for commercial banks to own large amounts of inert bank reserves rather than regulatory-friendly HQLA bonds, let’s revisit our QE example to understand how the Portfolio Rebalancing Effect really works.

In our stylized example, the commercial bank HQLA portfolio will consist of a bunch of inert bank reserves which don’t generate much returns and can’t be used to hedge interest rate risk: quite a suboptimal composition, wouldn’t you agree?

Hence, they will be looking to rebalance their portfolio towards a better composition of regulatory-friendly bonds and reserves: they will go and buy Treasuries, MBS, Corporate Bonds and so on and so forth.

But wait a second: the Central Bank is already (!) buying these exact same bonds with QE, isn’t it? Yes, exactly.

Summarizing, here is the virtuous cycle behind the Portfolio Rebalancing Effect.

Central Banks expand their balance sheet and purchase government bonds, and often also corporate bonds and mortgage-backed securities;

Commercial Banks are on the (forced) receiving end of QE, and hence their portfolio composition gets skewed towards more reserves, and less bonds;

But reserves are sub-optimal to own compared to regulatory-friendly bonds for the reasons we discussed, and hence they look to rebalance their portfolios;

They start buying the very same bonds QE is buying, hence suppressing volatility further and compressing credit spreads across the board;

Other banks who have resisted the temptation have now held inert bank reserves for a while and missed on the ‘‘carry’’ party, and given the reduced volatility pile on and rebalance their portfolio too;

Asset allocators and investors across the world are more and more encouraged to take additional risks in their portfolio, supporting the flow of credit and capital.

I know you want to chime in here or ask questions, so here is your comment button! :)

Conclusions (and a Q&A on Bank Reserves)

Ok, cool: this is one of the main reasons why Central Banks embark in QE.

Through the Portfolio Rebalancing Effect, they hope the flow of credit and capital will proceed smoothly and hence economic activity and aggregate demand will consequently pick up and ultimately support an increase in inflationary pressures.

But now, what the hell are these bank reserves useful for?

It’s time to answer once and for all the Top 5 FAQ on bank reserves.

Q1: What are bank reserves and who can own or transact with them?

A1: Bank reserves can be thought of as money for banks. You can own and transact in bank reserves only if you have a master account at the Central Bank. Unless you have one, you can’t transact with reserves. Also, reserves are a liability of the Central Bank and have no legal tender as real-economy money.

Q2: Can reserves be lent to the real economy?

A2: No. Banks don’t lend reserves. Banks create money out of thin air every time they make a new loan: they credit your bank account with money that never existed. They don’t use reserves in the process.

Q3: Yes, but if I withdraw cash from an ATM I am turning reserves into real-economy money I can spend. Right?

A3: No. When you withdraw cash from an ATM you are converting your digital bank deposits into bills, which is transforming an existing form of real-economy money (your bank deposit) into another form of real-economy money (cash).

Q4: What are the usual activities banks carry via reserves?

A4: They mostly settle payments against each other. Again, reserves are basically money for the commercial banking system.

Q5: Can banks buy bonds or equities with reserves?

A5: Yes, they can. The reallocation of reserves into Treasuries, corporate bonds or a selected number of stocks is what we defined as the portfolio rebalancing effect. They can also lend reserves in repo or FX swaps.

And this was all for today.

Thanks for reading all the way through, you are my hero! :)

Last but not least: if you are interested in any kind of partnership, sponsorship, or in bespoke consulting services feel free to reach out at TheMacroCompass@gmail.com.

May I ask you to be so kind and click on the like button and share this article around, so that we can spread the word about The Macro Compass?

It would make my day!

For any inquiries, feel free to get in touch at TheMacroCompass@gmail.com.

For more macro insights, you can also follow me on LinkedIn, Twitter and Instagram.

Feel free also to check out my new podcast The Macro Trading Floor - it’s available on all podcast apps and on the Blockworks Macro YouTube channel.

See you soon here for another article of The Macro Compass, a community of more than 53.000 worldwide investors and macro enthusiasts!

DISCLAIMER

The information provided on The Macro Compass newsletter is for general information purposes only. No information, materials, services, and other content provided in this post constitute solicitation, recommendation, endorsement or any financial, investment, or other advice. Seek independent professional consultation in the form of legal, financial, and fiscal advice before making any investment decision. Always perform your own due diligence.

Share this post