Good Sunday, and welcome back to The Macro Compass.

Macro will dominate the next decade, and plenty of investment opportunities should consequently arise for macro investors.

This is why I am working on the launch of my own Macro Fund!

Early investors receive a very preferential fee treatment they carry on forever, and FREE access to my flagship macro research.

But over 50% of the available spots for early investors are now already filled.

In case you’d want to secure your spot before it’s too late, send an email to fund@themacrocompass.com and I will share with you a memo with more info.

The minimum allocation to be eligible as an early investor is $250k.

People handle money every day.

But they barely understand how our monetary system really works.

Universities, economists and mainstream media keep perpetrating false myths:

''Central Banks print money and cause inflation''.

''The US must pay back its debt or it it will go broke''.

In the past 3 years I have produced several pieces to debunk these myths.

But I’ve never written a condensed primer on how money really works.

So, here is my best attempt at a short note that should provide you with the most important basics and framework to understand our monetary system.

Financial Money & Real-Economy Money

There are two main different tiers of money: financial money and real-economy money.

That's your easy way to think about what operations are potentially inflationary and which ones are asset-price-inflationary only.

Who prints financial and real-economy money?

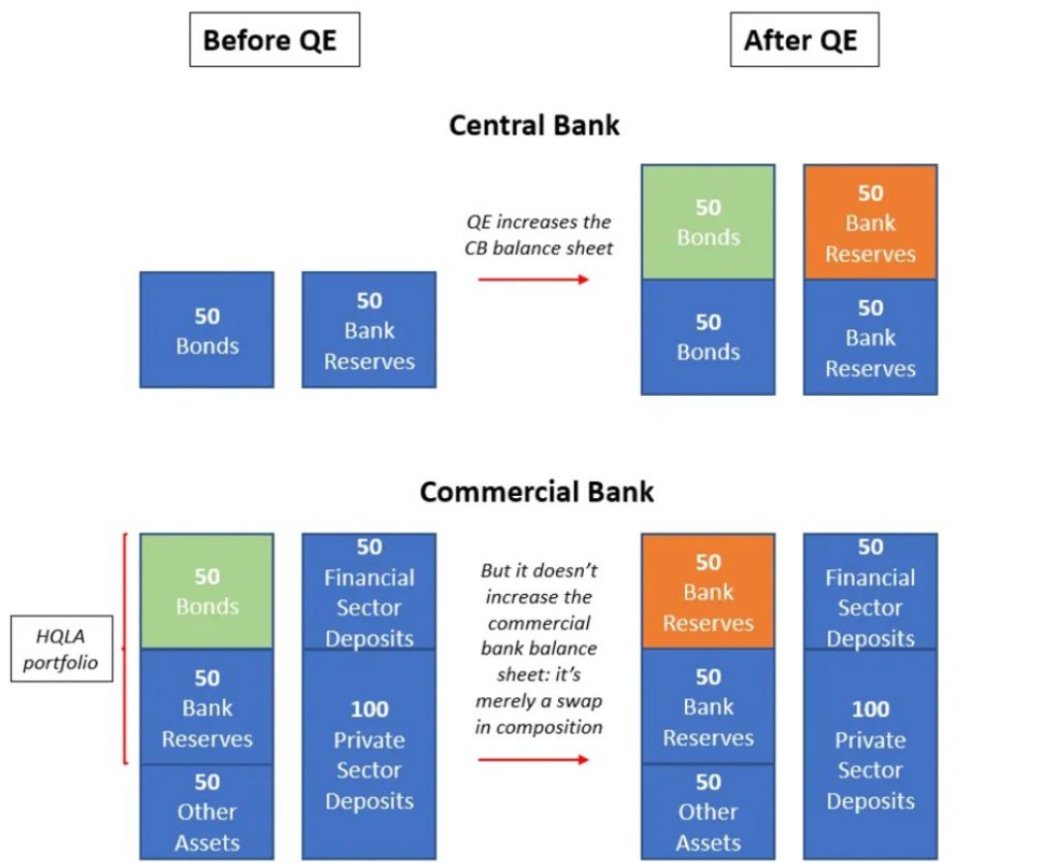

Financial money is printed by Central Banks, for example via QE.

The Central Bank changes the composition of the asset side of the financial institutions' balance sheet: it takes away bonds, and swaps them for reserves.

Bank reserves are financial money.

Now, the trick is that reserves are NOT money for the private sector: they are money for banks.

Banks DON'T lend or multiply reserves.

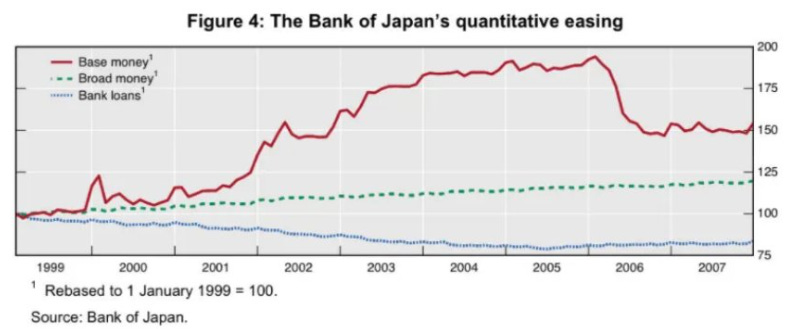

Reserves (red) in Japan doubled (!) in the 90s as the BoJ went on with QE, and yet bank loans (blue) shrank by 25% in the same period.

QE (financial money printing) does NOT encourage banks to lend more (real-economy money).

When lending, banks look at:

The creditworthiness of the borrower

The loan yield

The required capital for the loan

If the trade-off amongst these features looks good, they lend. Otherwise they don't.

A large amount of reserves has a virtual zero impact on the willingness and ability of commercial banks to make more loans.

Later, we will see how lending does not involve ‘‘multiplying’’ reserves either.

So why do Central Banks print financial money (i.e. reserves)?

Central Banks print new financial money (e.g. QE) to add interbank liquidity (reserves) to the system in periods of financial market stress.

This helps banks to have more liquid balance sheets, transact with each other better, and stabilize repo markets.

Think of it like ‘‘oiling’’ the monetary plumbing mechanism.

But remember this: financial money can NEVER enter the real economy.

So, who prints real-economy money instead?

Governments (via deficits) and banks (via lending).

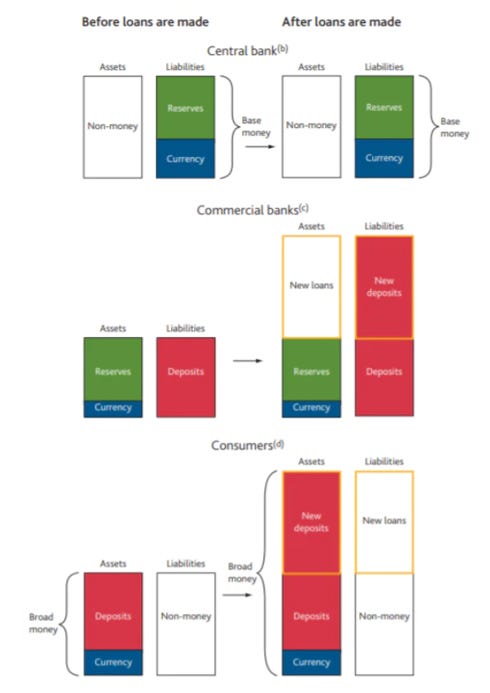

As the Bank of England itself shows, when making new loans banks literally credit your account out of nowhere and hence create new deposits.

You are getting credit against your future ability to generate cash flow.

You can now spend a lot of money in the real economy.

Please notice how banks are not ‘‘multiplying’’ reserves when lending: the green box for reserves plays a completely passive role in the lending process.

The banking system in aggregate creates new credit (loans), which is real-economy money that after being spent (for example to buy a house) ends up on the account of the house seller as a new bank deposit (red).

Lending expands banks’ balance sheets and it creates new real-economy money.

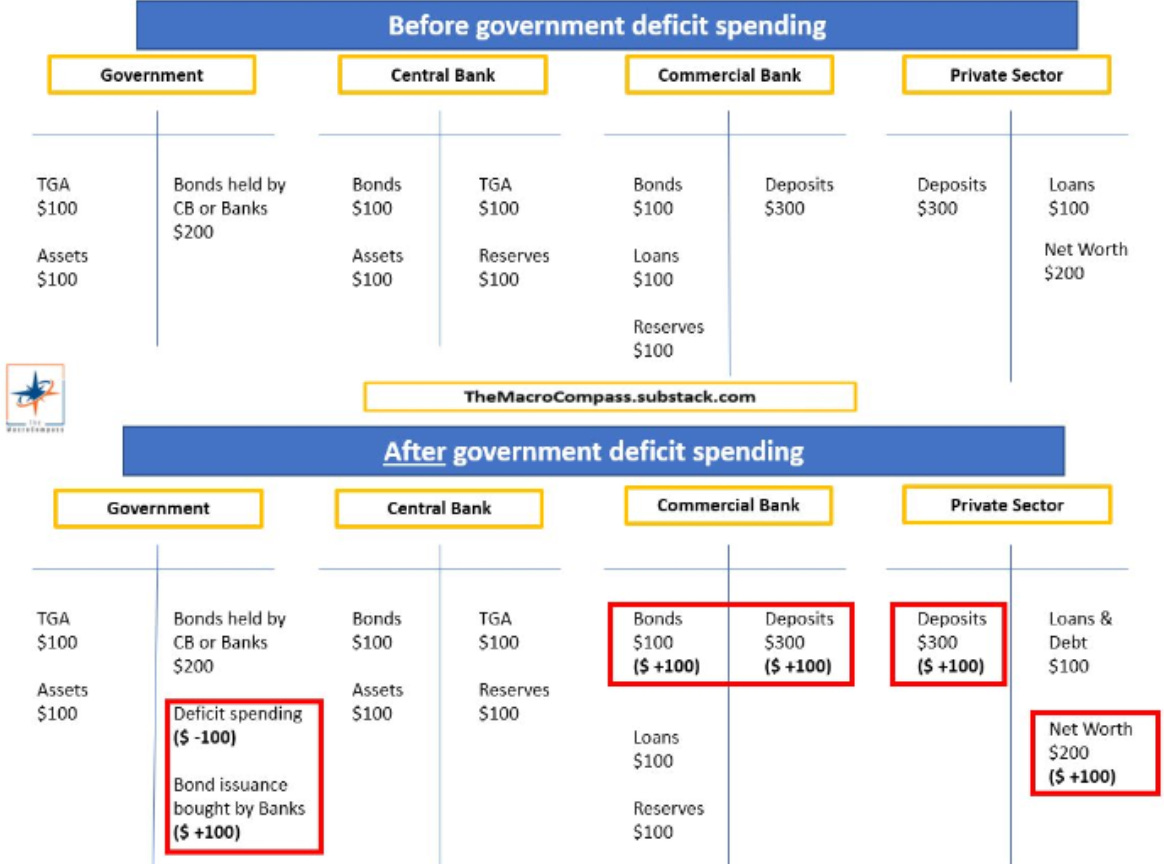

Government deficits also inject new spendable money for the private sector.

If the government spends more than it collects taxes for, new money has been created.

Deficit spending increases the net worth of the private sector without adding a liability to it.

What happens when the government goes for the so-demonized deficit spending?

The government blows a hole in its balance sheet, effectively creating negative equity through deficit spending – public opinion would say it spent money it didn’t have, and hence it must borrow (issue bonds).

But have a look at what the government really did.

The government spent $100 by sending cheques home to people (private sector), which all of a sudden find their bank deposits have gone up by the same $100 without any liability (!) immediately attached to it.

In other words, the government blew a hole in its balance sheet but increased people’s net worth!

Governments create the very money the private sector uses, so it does not ‘‘need’’ to save or find money before it spends.

Our self-imposed accounting rules require deficit spending to be ‘‘financed’’ by bond issuance, which banks can just absorb swapping reserves for bonds.

In one picture, here is your REAL ECONOMY money printers.

Banks - when they lend aggressively to the private sector, creating new credit which can be spent.

Governments - via deficit spending: cutting taxes or sending cheques so households and corps can spend more.

Now you see why all they told you about money printing is wrong.

Central Banks DO print money - but financial money, which is not inflationary.

And if the US would ''pay back all its debt'', it would subtract huge resources from the private sector - easier said than done!

The Dangers of Excessive Real-Economy Money Printing

Government deficits and bank lending increase the spending power of the private sector in a meaningful way.

It would be nice to receive cheques from the government each year, or to get cheap loans for years on end.

But what’s the main danger of excessive real-economy money printing?

Inflation.

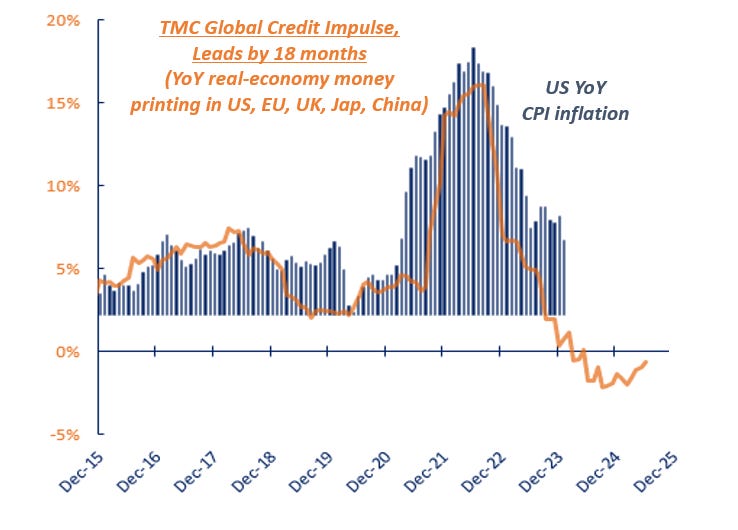

My global credit impulse index (orange) measures the amount and the pace of real-economy money printing in the 5 largest economies in the world.

It leads rapid changes in inflation with an 18 months lead-time.

The coordinated, gigantic fiscal and credit expansion of 2020-2021 culminated in excessive real-economy money printing which led to a vicious inflation spike in 2022.

The limits to government deficits and credit creation are inflation and real resources.

Excessive deficit spending and bank lending create too much money for the private sector, and if the supply of labor and real resources can’t expand rapidly enough we get sharp bouts of inflation.

Conclusions

People handle money every day.

But they barely understand how our monetary system really works.

Universities, economists and mainstream media keep perpetrating false myths:

''Central Banks print money and cause inflation''.

''The US must pay back its debt or it it will go broke''.

The reality is that there are two different tiers of money: financial money and real-economy money.

Central Banks do print money - but financial money, which is not inflationary.

The amount of financial money has zero influence on the real economy.

Financial money printing is used to oil the monetary plumbing mechanisms.

Governments (fiscal deficits) and banks (lending) print real-economy money.

They can increase the spending power of the private sector in a meaningful way.

But the risk of excessive real-economy money printing is inflation.

Excessive deficit spending and bank lending create too much money for the private sector, and if the supply of labor and real resources can’t expand rapidly enough we get sharp bouts of inflation.

Understanding money will be crucial for investors, and macro investment opportunities will abound over the next decade!

This is why I am working on the launch of my own Macro Fund.

Early investors receive a very preferential fee treatment they carry on forever, and FREE access to my flagship macro research.

But over 50% of the available spots for early investors are now already filled.

In case you’d want to secure your spot before it’s too late, send an email to fund@themacrocompass.com and I will share with you a memo with more info.

The minimum allocation to be eligible as an early investor is $250k.

The Truth About Money