If you have been around for the last 10 years as a global macro investor you have experienced a situation where the US stock market was pretty much the only game in town.

Since 2010 US stock markets largely overperformed Emerging Markets:

In the investment world, recency bias is strong and people assume this has always been the case.

Yet taking a 70+ years historical perspective the evidence is much more mixed: for instance, the chart above shows the impressive EM outperformance in the 70s-80s or the early 2000s.

The next decade is likely to see a multi-polar world with geopolitical fragmentation, a bigger role for commodities, ongoing demographics and political shifts and increased US inflation and growth volatility.

All these factors point to same conclusion: owning Emerging Market exposure in a long-term macro portfolio is a sensible thing to do.

Yet Emerging markets were (and still are) seen only as an exotic addition to portfolios: a 2020 survey by Morningstar shows only 7% of global portfolio allocations are dedicated to Emerging Markets.

For reference, EMs represent about 15% of the MSCI All Country World Index (ACWI) and account for almost 40% of global GDP!

In other words: suffering from recency bias, global investors are largely under-allocated to EMs despite reasonable valuations and macro conditions in place for solid returns over the next decade.

Ok, but which Emerging Markets to invest in and why?

This article provides you with a framework to approach long-term EM investing, and it points to three of my favorite Emerging Markets to own for the next decade.

We assess the most palatable Emerging Markets to invest in through fundamentals and valuations: countries with the best fundamental score and cheapest valuations make it to the shortlist.

The focus is on EMs where sufficiently accurate data is available.

The scoring model on fundamentals is based on 4 main pillars:

Economic growth (25% weight)

Institutional credibility (25% weight)

Leverage (25% weight)

External vulnerabilities (25% weight)

Here is the summary table on fundamentals:

Structural growth is a function of productivity and labor force growth – both are used in our analysis. We also look at the last 10-year average realized GDP per capita as a concrete measure (not a forecast) of recent economic performance in each EM – remember take the Chinese number with a pinch of salt.

Eastern Europe (Poland, Hungary) and some Asian countries look good, while an ageing population and uneven allocation of resources in Brazil and South Africa don’t look promising for growth.

Countries can grow organically but they can also make productive use of leverage to boost growth: for this reason private and public debt are both part of our assessment.

China is pretty much tapped out on leverage, and some other Asian countries (Thailand, Malaysia) also score poorly – recency bias again as the 1997 crisis seems to have been quickly forgotten?

On the other hand Indonesia, Mexico, Poland and Turkey have leverage space to boost growth going forward.

Now a crucial point: investors hate volatility and unpredictability.

Organic or credit-driven growth matters, but institutional credibility is key for investors: a 2015 paper from Lehkonen shows how political instability is negatively correlated with long-term EM returns.

To assess institutional credibility we have blended four relevant World Bank indicators (government effectiveness, regulatory quality, rule of law, and political stability) into one index and ranked EM countries.

Additionally, we reckon investors also assess policymakers’ credibility by their ability to keep inflation in predictable ranges – countries with the highest inflation volatility tend to be penalized by investors.

We have therefore also ranked countries by their 10-year average standard deviation of CPI prints.

Combining these two metrics the worst performing countries are (unsurprisingly) Turkey and Argentina, while ex-China Asian countries rank well – particularly Malaysia and Indonesia given their predictable inflation ranges and good institutional frameworks.

Finally, it’s important to recognize that most EM countries have external vulnerabilities: either they owe to the rest of the world through a negative current account or through a net negative investment position (NIIP).

Against this backdrop, EM countries will own a buffer of foreign exchange reserves (mostly USD and EUR) they can use to balance out their external vulnerabilities: we measure how many months of imports can be covered by the amount of net FX reserves each country has.

Turkey is notoriously vulnerable to external shocks, while China has amassed a gigantic amount of net FX reserves – actually even more than publicly disclosed.

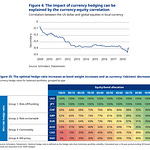

It’s now time to blend together the fundamentals and valuations so we can derive actionable conclusions.

The x-axis represents the country fundamental score: right is good, left less so.

The y-axis looks at equity market valuations: up means cheaper valuations, down = more expensive.

The top-right quadrant is the place where to look for bargains.

Remember: the EM complex is under-owned and it’s overall a cheap and sensible exposure to have.

From a relative perspective, EMs look fairly priced against our fundamental models yet the blue circle highlights some interesting opportunities in this universe.

My final shortlist includes 3 countries: Poland, Malaysia, and Indonesia.

Indonesia is home to over 20% of global nickel reserves (essential in the EV-making process) and it has effectively banned the unprocessed export of nickel hence trying to force companies to set up plants locally and boost the country’s long-term growth perspectives.

Even if this protectionist tactic could somehow backfire, it goes to show how Indonesia could attract more investments going forward.

Malaysia is also a net commodity exporter and the new government is keen on applying structural reforms too.

We are talking about a country with 10 years of positive current account balance and a credible policymaking mix which has now lured Tesla to engage in business relationships.

Finally my darling Emerging Market: Poland.

Over the last 5 years Poland has managed to beat most of its European peers in GDP per capita growth, and its potential long-term growth has also been boosted by a large influx of Ukrainian immigrants.

Poland is a productive economy with a long-standing and specialised manufacturing sector which will be increasingly targeted for ‘’friend-shoring’’.

The country has also emerged as the 5th world largest producer of EV batteries.

The cherry on the cake is a newly elected coalition government led by Donald Tusk (former President of the European Council) which will replace the former European-critic government: a more friendly stance towards Europe will unlock further inflows of direct and portfolio investments towards Poland.

Turkey also is a high-potential investment trading at super cheap valuations and with strong demographics fundamentals, but policymakers credibility remains too low.

Concluding: investors suffering from recency bias can’t see beyond US equity markets but macro conditions and cheap valuations favor a long-term allocation to EMs.

The entire space is interesting with Poland, Indonesia and Malaysia the most compelling countries.

This week, I am also sharing with you a global macro presentation I gave for institutional clients where I covered the Fed, China, Japan, bond markets and more.

Click Here to watch it.

If you’ve enjoyed this piece, please smash the Like button and Share it with a friend!

Share this post