If a couple of regional banks were so bad at managing their interest rate risk and deposit outflow risk to blow up in a few hours, how can we really be sure other banks won’t face similar problems?

Having run a large investment portfolio at a European bank and been part of the management for the Treasury department, I will try to use my practical experience to provide you with:

A quick primer on how banks approach risk management of a large securities portfolio;

A level-headed analysis of the damage that higher interest rates do to a banks’ balance sheet, and the resulting assessment of broad contagion risks;

An update on inflation and the likely Fed reaction function in this environment.

Banks buy bonds for two main reasons: clipping coupons and regulation.

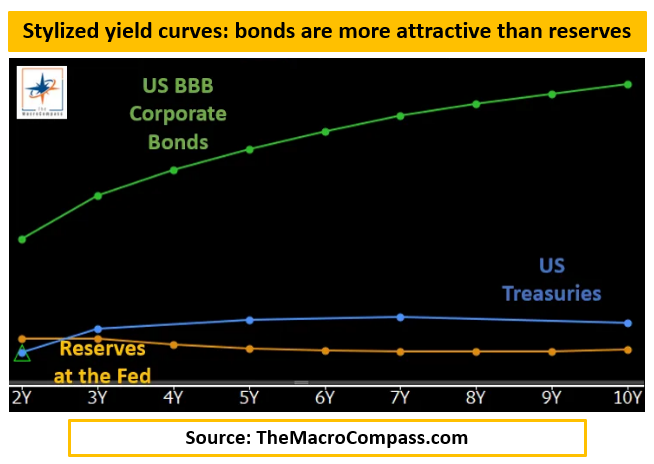

When you attract deposits and do nothing on the asset side, you are going to accumulate reserves at your domestic Central Bank.

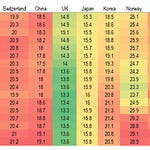

But banks want to make money, and bonds generally yield more than Central Bank reserves (chart below).

Sum up regulation (LCR) forcing large banks to own ~20% of their balance sheet in liquid assets (read: bonds) and there you go: banks have huge investment portfolios to clip coupons and meet regulation.

How do banks approach the risk management of such gigantic portfolios?

A prudent bank hedges most if not all its interest rate risk coming from the securities portfolio with swaps.

The bank buys bonds (receives fixed rate) and pays swaps (pays fixed rate) against them as a hedge.

Banks earn the (credit) spread between bond yields and swap yields, and that’s it.

But now comes the trick: accounting.

Swaps are derivatives, and their standard accounting treatment is to directly hit the P&L of the bank hence causing quite some immediate volatility for the financial results of the bank.

Banks don’t like that at all.

That’s why the regulator allows for something called hedge accounting: if you buy bonds and put them in Available-For-Sale (AFS) and use swaps to hedge the interest rate risk, all that P&L volatility is gone.

The small volatility of offsetting bonds and swaps hits the capital position of the bank.

Easy-peasy, no drama: little volatility as risks are hedged, and friendly accounting treatment (no P&L vol).

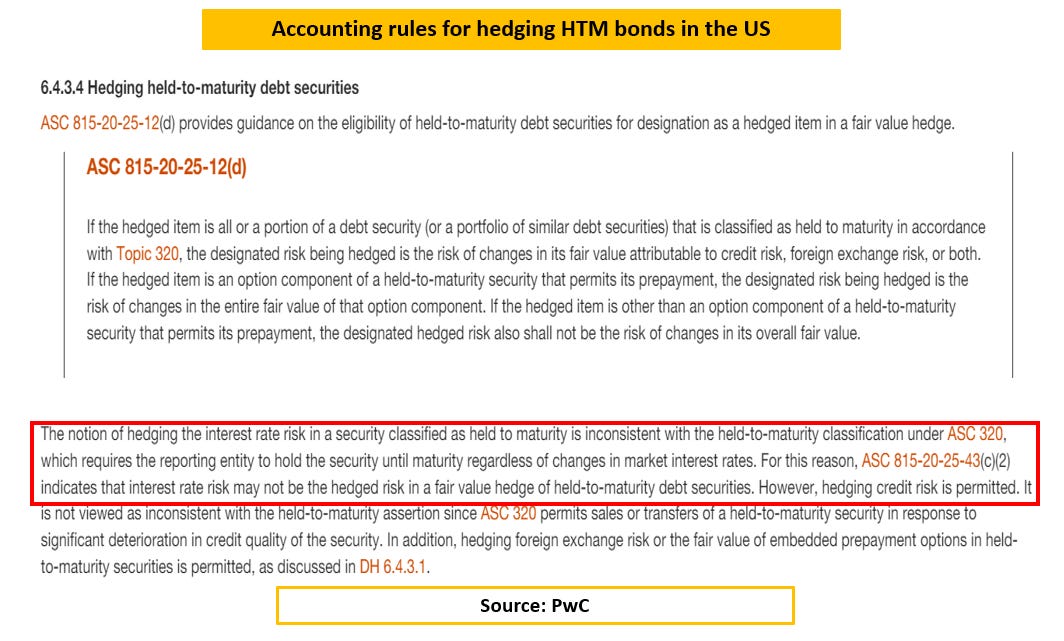

But what happens if you book bonds in Held-To-Maturity (HTM) instead?

In the US, once you book bonds in HTM the accounting rules are such that hedging the interest rate risk on these bonds is quite punitive.

Swaps hedging HTM bonds do not receive the friendly accounting treatment and hence hit the P&L of the bank – but bonds don’t, which creates a massively inconvenient asymmetry and P&L vol that banks hate.

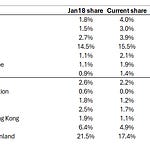

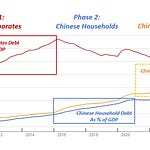

The result is that US banks end up NOT hedging the interest risk on HTM bonds.

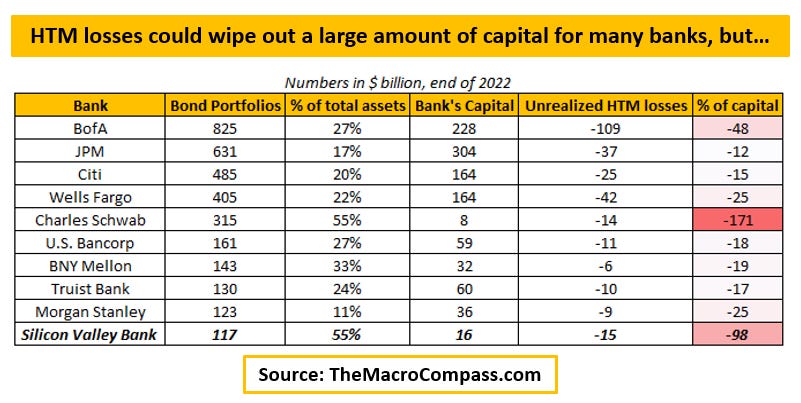

This is important because the HTM losses accumulated on these bonds can be very large.

P.S. My spreadsheet failed me on Schwab. The bank’s capital is 25+ bn, not 8. Hence losses are about 50%+ of capital, not 171%.

Even for systemically important banks like Bank of America these losses could wipe out half of their capital!

So, are large US banks at risk of going belly up too?

And given today’s inflation print, what will the Fed do?

Let’s dig in…

Enjoyed it so far and eager to read the remaining part of this macro report?

Come join The Macro Compass premium platform to get access to Alf’s full-length timely pieces, actionable investment strategy and much more!

Check out which subscription tier suits you the most using the link below.

For more information, here is the website.

Share this post