‘‘When you combine ignorance and leverage, you get some pretty interesting results’’

Warren Buffett

Real interest rates were in a secular declining trend centuries before the Federal Reserve or other central banks were established.

That’s because the most important drivers of long-term real yields are to be found more in demographics and productivity trends than in monetary policy decisions.

But why are real interest rates so important?

Leverage is the very backbone of our credit-based monetary system.

Real interest rates determine how cheap or expensive economic agents find the access to new credit to be, and what matters the most is their level relative to the equilibrium real interest rate.

In this piece, we are going to discuss the importance of real interest rates, their long-term drivers and trends and the interaction between monetary policy and the equilibrium real rate r*.

Without further ado, let’s jump right in!

It’s Going Down, For Real

In the introductory piece of my Bond Market 101 Series, we discussed how the first way to deconstruct bond yields such that you really understand what’s going on under the hood is:

Real yields are the barometer of how cheap or expensive is the inflation-adjusted cost for the marginal economic agent to incur into more leverage.

Now, the first thing I want to clarify is that you cannot calculate real yields as 10-year nominal yields minus today’s YoY inflation figures.

Long-term nominal yields incorporate long-run expectations (and risk premium) for inflationary pressures, so comparing them to the latest YoY CPI figure makes very little financial sense.

If you have one, think about your own 10y+ fixed-rate mortgage: what you really care about is for inflation-adjusted servicing cost over the lifetime of the mortgage.

When it comes to assessing how cheap or expensive incremental borrowing will turn out to be, it’s all about assessing future CPI: hence, inflation expectations matter much more than today’s CPI print.

Ok, but why are real yields so important in the first place?

We operate in a fully elastic credit system that allows governments and commercial banks to create new resources for the private sector (e.g. ‘‘money’’) out of thin air and without an explicit hard peg.

For instance, when commercial banks lend they increase their balance sheet by extending a new loan (white stack with orange borders up) and crediting the consumer’s account with a new bank deposit (red stack with orange borders up).

The private sector now has more spendable ‘‘money’’ (bank deposits) and can hence contribute to a pick-up in cyclical economic growth.

Government deficits work in a similar way: the government pumps net resources into the private sector (think of stimulus checks) by expanding its balance sheet and it doesn’t plan to tax them back.

More spending capacity for the private sector, again.

Cool, right?

Wait a second: the flipside of credit creation is debt, though.

And we have been pretty good at this game across the world over the last 40 years.

The private sector balance sheet also has liabilities (debt) and private economic agents must be able to service these obligations with their long-term cash flow and earnings generating abilities.

It’s all about balance: real yields measure the inflation-adjusted cost for the marginal economic agent to access this newly created credit, which must then be serviced with the long-term ability to generate earnings.

A quick look at 700 years of history of real interest rates reveals that the declining trend started way before Central Banks were even a thing.

So, what are the drivers behind the secular decline in real yields?

Poor demographics and stable but low productivity growth.

Except for the the post-WWII period between 1950 and 2000 when the world’s population grew at about 1% per year, we historically grow our population at yearly rates < 0.5% and the latest United Nations forecast point to 0% world’s population growth by 2050-2070.

As world’s population numbers struggle to go meaningfully up and our society ages too, the labor force tends to stagnate or even shrink in some jurisdictions.

The productivity of capital and labor force has hovered around 0-2% for centuries: we become more productive year after year, but at a relative slow pace when we consider the aggregate economy.

Central Banks are not the cause of structurally low and declining real yields: they merely calibrate monetary policy to achieve their goals in such a secular environment.

It’s All About the Equilibrium

As the structural drivers of the economic growth needed to service an increasingly high leverage remain poor, real yields tend to decline to allow the marginal economic agent to access new credit at affordable costs.

It’s all about equilibrium, really.

In order to ensure economic growth and price stability, Central Banks are very attentive to this balance and monitor a metric called equilibrium real interest rate or R-star.

R-star measures the (unobservable) real interest rate at which an economy runs at its own potential growth rate without overheating or unduly cooling down.

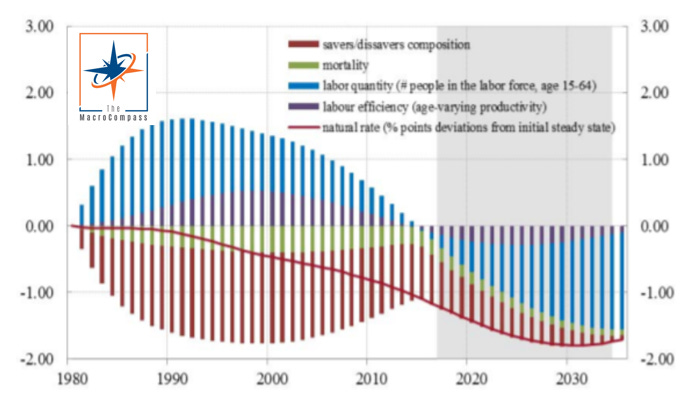

Here are the R-star drivers and future trends in Europe according to the ECB.

The most important drivers are related to demographics:

Growth rate in labor supply (blue): lower birth rates and ageing population lead to a shrinking number of people in the labor force

Savers/dis-savers composition (red): an ageing population with a longer life expectancy will tend to save more

Mainly due to demographics, the ECB expects the natural (or equilibrium) interest rate to drop by another full percentage point over the next decade or so.

Central Banks calibrate their monetary policy to facilitate economic growth, employment and price stability.

As R-star secularly declines, Central Banks have no other option rather than cutting policy rates in an attempt to keep monetary policy from becoming restrictive.

This bring us to the interconnection between monetary policy and real rates.

To truly grasp is monetary policy is accommodative or restrictive, you shouldn’t look at prevailing real yields in a silo.

Instead, you should compare those short/medium term real yields to the equilibrium real interest rate (R-star).

If real yields are sufficiently lower than r*, the marginal economic agent will find the access to credit cheap enough: she will more easily lever up, boosting cyclical economic growth and hence earnings.

If real yields are higher than the equilibrium r*, the private sector will find it prohibitively expensive to access new credit and likely behave more defensively: cyclical growth and hence earnings will slow down, and so will risk assets.

The chart above shows US 5y real yields minus R* (blue) and the S&P500 YoY performance lagged by 6 months (orange).

Every time 5y real yields approach or increase above the equilibrium rate r* (blue line crosses the zero threshold on the upside), with 6 months lag risk assets performance tends to disappoint.

Monetary policy had become too restrictive relative to the equilibrium rates the economy could take: less access to credit, less cyclical earnings, more defensive behavior from the private sector = hit to risk assets.

For the record, my estimate for R* in the US sits around 0%.

Conclusion

Our credit-based monetary system relies on ever increasing leverage to generate politically and socially acceptable rates of economic growth.

Real interest rates determine how cheap or expensive economic agents find the access to new credit to be, and therefore are a key variable to understand when approaching bond markets.

Real interest rates were in a secular declining trend centuries before the Federal Reserve or other central banks were established.

That’s because the most important drivers of long-term real yields are to be found more in demographics and productivity trends than in monetary policy decisions.

Central Banks are not the cause of structurally low and declining real yields: they merely calibrate monetary policy to achieve their goals in such a secular environment.

As R-star secularly declines, Central Banks have no other option rather than cutting policy rates in an attempt to keep monetary policy from becoming restrictive.

Actually, the few times real yields were allowed to go higher than the equilibrium r*, cyclical growth and risk assets disappointed hence forcing Central Banks to pivot back to a more accommodative stance in an attempt to achieve their objectives.

If you understand how our credit-based monetary system works and keep track of real yields relative to r*, I can ensure you are about to become a more intelligent investor.

If you enjoy my work, please consider clicking on the like button and share the article.

It costs you literally nothing, but it would really make my day!

Are you looking for any other kind of partnership or collaboration?

Are you an institutional investor who likes The Macro Compass and would be interested in a bespoke, pro-to-pro coverage?

Feel free to get in touch at themacrocompass@gmail.com.

See you soon!