Hi all, and welcome back on The Macro Compass!

Quick reminder: from January 1st, getting access to this content (and much more!) will require a paid subscription.

As a loyal TMC reader, there is an exclusive offer for you: get in now and pay only 8 months instead of 12!

The offer is time-limited: it runs for only 3 more days, and out of the 2,000 available spots only 145 are left (~20 for Pro subscribers).

Last round: check out which subscription tier suits you the most and take advantage of this exclusive offer before Nov 30!

All They Told You About Money Printing Is Really, Really Wrong

Without properly understanding money, it’s basically impossible to connect the countless dots of the global macro puzzle.

Yet, we assume we know all about money: universities and mainstream economic courses teach us that governments need money to fund their spending, Central Banks have the authority to print money we use, and commercial banks lend and multiply customers’ money in a fractional reserve banking system.

That’s literally all wrong.

Our monetary and credit system envisages two distinct tiers of money: real-economy money (potentially inflationary) and financial-sector money (potentially asset-price inflationary).

Governments and commercial banks have the ability to print real-economy money.

Central Banks have the ability to only print financial-sector money.

In this article we will:

Discuss the two main forms of money: real-economy and financial-sector money;

Go through the basic mechanics of real-economy and financial-sector money printing, and debunk the most common ‘‘money printing’’ myths;

Summarize the implications for markets ahead.

Real-Economy Money & Financial-Sector Money

Let’s first define the two main tiers of money, and why do we care about them from a global macro asset allocation point-of-view.

Real-economy money is the one used by non-financial private sector agents (e.g. households, corporates) to make transactions tha contribute to economic activity.

The more real-economy money out there, ceteris paribus the more likely economic growth will be stronger.

Also, a rapid increase in real-economy money at a time when the supply of goods and services can’t keep up will most likely generate strong inflationary pressures.

In other words, rapid changes in the amount of real-economy money anticipate rapid changes in economic growth and inflation - pretty relevant for asset allocation.

Financial-sector money is the one used by financial entities: mostly banks, but also pension funds, asset managers and so on.

The more financial-sector money out there, the more likely financial agents will be over time to engage in riskier activities and to chase riskier assets in an attempt to generate better returns.

In other words, the level and rate of change of financial-sector money informs us about the attitude that financial institutions are likely to have towards taking risks.

Now, who prints what form of money and how does it work?

#1: Banks & Governments Print Real-Economy Money

Nowadays, given that in many jurisdictions cash transactions only account for < 5% of total we can state that real-economy money is mostly bank deposits held by the non-financial private sector (read: mostly held by us).

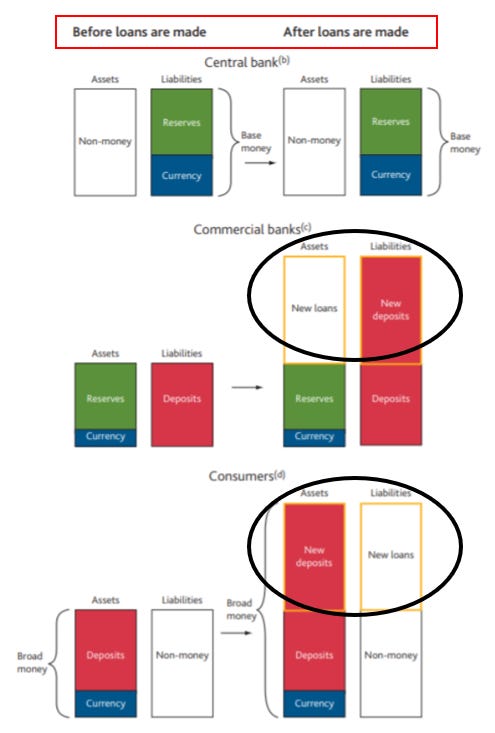

Every time commercial banks make a loan, new real-economy money is created.

Banks don't lend reserves or existing deposits: as the Bank of England itself shows, when making new loans banks expand their balance sheet and literally credit your account out of nowhere.

By doing so, they create new deposits for the non-financial private sector (e.g. people).

Does this mean banks can just print as much money as they want?

Not really: banks are private capitalistic entities which need to maximize RoE for their shareholders and act within the tight boundaries of regulation.

This means banks decide about their lending activity looking at these criteria:

The creditworthiness of the borrowers

The attractiveness of loan yields

The required capital and balance sheet costs (i.e. regulatory constraints)

If there is a good trade-off amongst these 3 variables, they lend. Otherwise they don't.

Did you notice how the amount of reserves they own is basically irrelevant in the decision-making process?

QE ≠ real-economy money printing: we will come back to this later.

Now, the other real-economy money printer is the government: come again?

If the government spends more than it plans to collect taxes for (deficits), in most cases new real-economy money has been created.

Government deficit spending increases the net worth of the private sector…without adding a liability to it!

Think about it: when the US government sent cheques to its citizens, American people literally saw the amount of their spendable money increase out of nowhere.

Deficit spending increases the amount of non-financial private sector deposits (i.e. real-economy money) as long as households don’t need to purchase the Treasuries issued by the government itself - which in most cases are anyway bought by financial institutions or the Central Bank.

This means deficit spending prints real-economy money, and it increases the net worth of the private sector as households don’t experience an increase in debt.

In other words, government deficits boost the financial wealth of the private sector.

As shown, banks and the government print real-economy money.

Credit creation boosts aggregate demand and it can lead to inflationary pressures.

That's exactly what we have seen in 2020-2021: massive fiscal deficits & government-sponsored bank lending ended up overheating the economy, resulting in super strong real GDP growth and inflationary pressures on top.

My Global Credit Impulse tracks the pace of real-economy money creation in inflation-adjusted terms in the 5 largest economies in the world.

As you can see: rapid changes in the amount of real-economy money anticipate rapid changes in economic growth - pretty relevant for asset allocation.

#2: Central Banks Print Financial-Sector Money

Central Banks can increase or decrease the amount of financial-sector money.

Via QE and other monetary policy operations, Central Banks print bank reserves - you can think of them as money for banks.

Banks use reserves to settle transactions and engage in monetary plumbing operations with each other: reserves can only be used by entities with a Central Bank account.

With QE, the Central Bank changes the composition of the asset side of the financial institutions' balance sheet: it takes away bonds, and swaps them for reserves. The interbank system as a whole can't refuse this transaction; there is always a marginal clearing price for QE transactions.

As said before, banks don’t lend reserves to the real economy: you can throw as many as you want to them, and it won't change their stance when it comes to lending.

Japan showed us that in the early 2000s already.

Bank reserves (red) doubled (!) in 5 years as the BoJ went on with QE, and yet bank loans (blue) shrank by 25% in the same period.

With double the amount of reserves, banks lent less.

The other important and less known form of financial-sector money is bank deposits held by non-bank financial institutions (e.g. asset managers, pension funds etc).

When the Central Bank purchases bonds from a pension fund via QE, the fund now owns less bonds (purple) but more deposits (red).

These deposits are not real-economy money: the pension fund can’t directly spend them in activities boosting nominal growth.

But it can use them to purchase other financial assets.

Bank deposits held by non-banks financial institutions are financial-sector money.

If financial institutions are deprived of their bonds and stashed with excess reserves or deposits, as long as volatility is low and the economy is not falling apart they will try to rebalance their portfolios back to risk assets over time.

The more financial-sector money out there, the more likely financial agents will be over time to engage in riskier activities and to chase riskier assets in an attempt to generate better returns.

This is why tracking levels and rate of changes in bank reserves and more broadly financial-sector money is very important for global macro asset allocation.

Conclusions

Real-economy money is the one used by non-financial private sector agents (e.g. households, corporates) to make transactions tha contribute to economic activity.

The more real-economy money out there, ceteris paribus the more likely economic growth will be stronger.

Also, a rapid increase in real-economy money at a time when the supply of goods and services can’t keep up will most likely generate strong inflationary pressures.

Governments and commercial banks print real-economy money, which we track via our flagship Global Credit Impulse index.

Financial-sector money is the one used by financial entities: mostly banks (reserves), but also pension funds, asset managers (deposits held by non-banks financial institutions) and so on.

The more financial-sector money out there, the more likely financial agents will be over time to engage in riskier activities and to chase riskier assets in an attempt to generate better returns.

In other words, the level and rate of change of financial-sector money informs us about the attitude that financial institutions are likely to have towards taking risks.

Where do we stand today?

The pace of creation of both financial-sector money (bank reserves in orange, left chart) and real-economy money (global credit impulse in blue, right chart) is pretty consistently pointing downwards.

The combination is generally negative for risk assets.

To wrap it up, one final thought about how ‘‘safe’’ is your money/deposit.

One good way to think about the safety of your money is to ask yourself: whose liability is my money?

A bank deposit < $250k: implicitly the liability of the US government (FDIC);

T-Bill investment: your money is the direct liability of the US government;

Bank deposit > $250k: your money is the unsecured liability of the bank;

Money parked on FTX: …

And this was it for today, thanks for reading!

If you enjoyed the piece, please click on the like button and share it with friends :)

Finally, a quick reminder: from January 1st, getting access to this content (and much more!) will require a paid subscription.

As a loyal TMC reader, there is an exclusive offer for you: get in now and pay only 8 months instead of 12!

The offer is time-limited: it runs for only 3 more days, and out of the 2,000 available spots only 145 are left (~20 for Pro subscribers).

Last round: check out which subscription tier suits you the most and take advantage of this exclusive offer before Nov 30!

Subscribing to any of the tiers above now will guarantee you lock-in early bird prices and your subscription will cover the entire 2023 calendar year.

For more information, here is the website.

I hope to see you onboard!

DISCLAIMER

The content provided on The Macro Compass newsletter is for general information purposes only. No information, materials, services, and other content provided in this post constitute solicitation, recommendation, endorsement or any financial, investment, or other advice. Seek independent professional consultation in the form of legal, financial, and fiscal advice before making any investment decision. Always perform your own due diligence.

Share this post